Tit-for-tat is one the simplest strategies when faced with a prisoner’s dilemma type situation. The only simpler strategies would be the pure strategies of “always cooperate” and “always defect”. Neither of these will be very successful.

Tit-for-tat has a simple basic concept.

A player using this strategy will initially cooperate, then respond in kind to an opponent's previous action. If the opponent previously was cooperative, the player is cooperative. If not, the agent is not.

The strategy was entered by Anatol Rappoport in the Robert Axelrod’s Tournaments and was the simplest and shortest strategy entered each time. The interesting thing was that the strategy of tit-for-tat can do no better than tie with an opponent if used in an iterated prisoner’s dilemma. Tit-for-tat never used an unprovoked defect to try and catch out an opponents. Tit-for-tat is nice – never the first to defect.

Using the example of goals scored in football league, tit-for-tat is a strategy that results in games that are 5-5 draws, 5-4 losses or at worst a 5-3 defeat against all opponents. Tit-for-tat beats nobody but is involved in lots of high-scoring games. Strategies that are ‘not nice’ win most games 2-1 or draw 1-1. Strategies that ‘not nice’ never get beaten but are involved in lower scoring games.

In a sport league points are accumulated by winning individual games. If the competition is about beating your opponent in each game then ‘not nice’ strategies will come out on top in the tournament. In life, business and most everyday settings the objective is not to beat your opponent but to be as well off as possible. This generally involved maximising the utility, profits or well-being earned.

If there was a sport league with the objective to have the highest number of goals a ‘nice’ strategy such as tit-for-tat is far better. Tit-for-tat might never beat anyone but even in defeat it earns more than ‘not nice’ strategies do in victory, if payoffs are counted in goals. Clearly, payoffs based on aggregate goals scored are not used to determine winners in football leagues, but in general life our well-being is defined by total payoffs than total wins.

Thus at the aggregate level tit-for-tat wins because the aggregate sum of the payoffs earned are greater. In the context of the Prisoner’s Dilemma tit-for-tat is involved in games with more cooperation so both players benefit from the mutual cooperation.

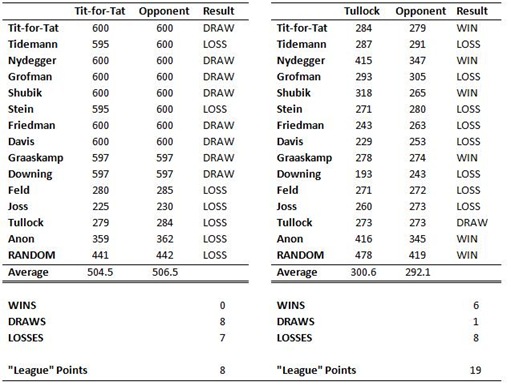

Here is a comparison of the performance of Tit-for-Tat and the entry by Nobel Prize winner Gordon Tullock in the first round of Axelrod’s tournament.

The first column of numbers gives the score for the named strategy in each game. The second score gives the score of the opponent as listed down the first column of the table. For example, the first row shows that when tit-for-tat played itself the result was a 600-600 draw. The next row tells us that when playing the strategy submitted by Tidemann that Tit-for-Tat lost 595-600. The same holds for the right hand side of the table which gives the performance of Tullock’s strategy.

We can see that Tit-for-Tat has an abysmal win/draw/loss record having no wins, eight draws and seven losses. With the traditional three points for a win, one for a draw, zero for a loss, Tit-for-Tat would score 8 league points from its 15 games. On the other side Tullock has a record of six wins, one draw and eight losses and would garner a much more impressive 19 points.

However, if we look at the average payoff earned by the strategies we see that even though Tit-for-Tat beat nobody it earned an average of 504.5 from the 15 games played. Tullock had a far better win/loss record but only earned an average of 300.6 from the 15 games played.

If these payoffs were profits, Tullock would have beaten far more of his opponents, but Tit-for-Tat would have earned far higher profits. Which company would you prefer to be a shareholder of?

No comments:

Post a Comment